Protecting Children Online

Topics Covered

Advanced Notices of Proposed Rulemaking

On August 1, 2024, the Office of the New York State Attorney General (OAG) released two Advanced Notices of Proposed Rulemaking (ANPRM) for the SAFE for Kids Act and the NY Child Data Protection Act. These ANPRMs are not part of the formal rulemaking process required by the NYS Administrative Procedures Act. However, this step allows our office to seek information from stakeholders before proposing formal rules.

These ANPRMs include an extensive series of questions for gathering important information from a broad range of stakeholders. We encourage all stakeholders to share any substantive feedback in writing so that it will be part of the official record. Submit your comments to ProtectNYKidsOnline@ag.ny.gov for the SAFE for Kids Act and ChildDataProtection@ag.ny.gov for the Child Data Protection Act.

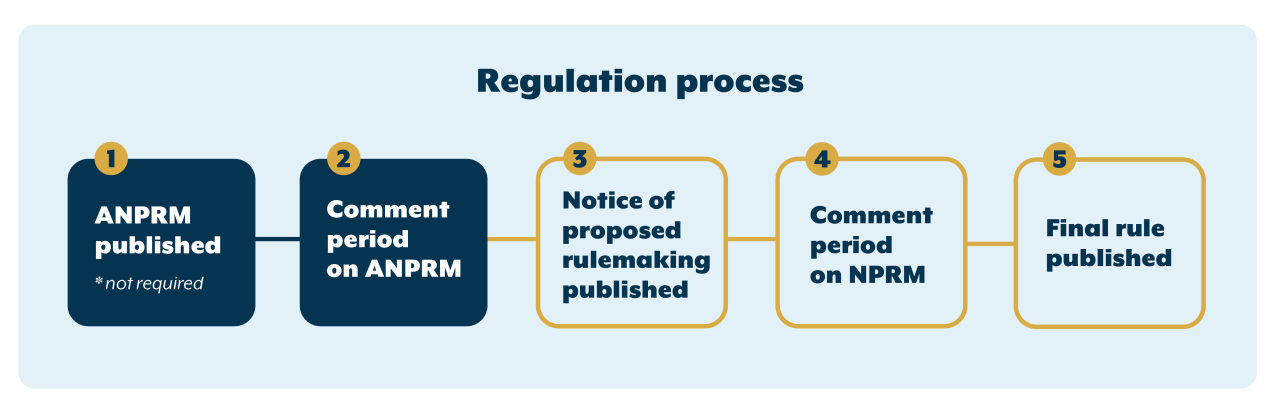

State Agencies Must Follow a Formal Process

The NYS Administrative Procedures Act sets out a formal process that every state agency must follow before its rule can become effective. The agency begins by submitting a proposed rule with the secretary of state for publication in the State Register. The public has no fewer than 60 days from the date of publication to provide comments on the proposed rule. Before a rule can become final, the agency must provide an assessment of the public comments received about the rule.

SAFE for Kids Act

Advanced Notice of Proposed Rulemaking pursuant to New York General Business Law section 1500 et seq.

The New York State Office of the Attorney General (OAG) is issuing this Advanced Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (ANPRM) to solicit comments, data, and other information to assist the office in crafting rules to protect children from the harms of addictive social media feeds, pursuant to New York General Business Law section 1500 et seq. (GBL section 1500).

The New York legislature passed the Stop Addictive Feeds Exploitation (SAFE) for Kids Act because New York children are in the midst of a mental health crisis caused by harmful social media use. The legislature found that social media companies have created feeds personalized by algorithms. These feeds can track tens or hundreds of thousands of data points about users to create a stream of media that is a perfect drip of dopamine. Such feeds can keep children scrolling for dangerously long periods of time (2024 N.Y. Laws ch. 120, section 2) Children, who are less capable than adults of exercising self-control, have been particularly susceptible to these addictive feeds. Many spend hours each day scrolling through social media feeds (Id.). The legislature found that these hours spent on social media have caused harm to New York children. The time spent on social media is ten times more dangerous than other kinds of screentime. Greater time spent on social media is correlated with increased rates of depression, anxiety, suicidal ideation, and self-harm (Id.).

To address this public health crisis, the SAFE Act prohibits social media platforms from providing minors with an addictive feed that uses data concerning that child (or the child’s device) to personalize the material the child sees, thereby extending time spent on social media to unsafe levels (GBL section 1500(1)). The legislature defined addictive feeds to not include personalization based on information “not persistently associated with the user or user’s device” that “does not concern the user’s previous interactions with media generated or shared by other users.” In addition, a feed is not addictive if it is based on “user-selected privacy or accessibility settings, or technical information concerning the user’s device;” express and unambiguous requests for “specific media, media by the author, creator, or poster of media the user has subscribed to, or media shared by users to a page or group the user has subscribed to;” or requests to block, prioritize, or deprioritize, such media, or where the media is “direct, private communications,” search results, or the “next in a pre-existing sequence.” (GBL section 1500(1)). The obligations in the law apply to a “website, online service, online application, or mobile application, that offers or provides users an addictive feed as a significant part of [its] services” (GBL section 1500(2)).

In addition to restricting social media platforms’ ability to provide addictive feeds to minors, the SAFE for Kids Act also includes provisions that ensure users will be able to obtain the benefits of the act without compromising their experience of social media or their privacy. Information used to determine age or obtain parental consent must not be used for any other purpose “and shall be deleted immediately after” such use (GBL section 1501(3), (5)). In addition, social media platforms may not “withhold, degrade, lower the quality, or increase the price” of their services because of their inability to provide a user an addictive feed (GBL section 1504).

The legislature also found that overnight notifications presented a public health risk. The SAFE for Kids Act therefore also prohibits social media platforms from sending “notifications concerning an addictive feed” to a known child between 12 and 6 a.m. without obtaining parental consent (GBL section 1502).

The legislature has charged OAG — which has significant experience with the harms of social media, privacy, and complex technical issues through its investigations and litigations, and through its in-house research and analytics team — with promulgating regulations before the statute can go into effect. The legislature gave OAG an express directive to promulgate regulations in three areas:

- Social media platforms are required to use “commercially reasonable and technically feasible methods” to determine if a user is a child before providing them with an addictive feed. The OAG is charged with promulgating regulations identifying such commercially reasonable and technically feasible methods, taking into consideration a number of factors (GBL section 1501(1)(a), (2)).

- If a user is a child, the social media platform must obtain “verifiable parental consent” before providing such with an addictive feed. The OAG is also charged with promulgating regulations identifying methods of obtaining verifiable parental consent (GBL section 1501(1)(b), (4)).

- The OAG is charged with promulgating any needed language access regulations (GBL section 1506).

In addition, OAG is charged with promulgating regulations to effectuate and enforce the Act as a whole.[1]

Questions for Public Comment

The OAG is issuing this ANPRM to solicit comments, including personal experiences, research, technology standards, and industry information that will assist OAG in determining what rulemaking will be most important to effectuate the purposes of the SAFE for Kids Act. The OAG seeks the broadest participation in the rulemaking, and encourages all interested parties to submit written comments. In particular, OAG seeks comment from interested parties — including New York parents and children, consumer advocacy groups, privacy advocacy groups, industry participants, and other members of the public — on the following questions. Please provide, where appropriate, examples, data, and analysis to back up your comments.

Submit comments to ProtectNYKidsOnline@ag.ny.gov by September 30, 2024.

- The SAFE for Kids Act requires social media platforms to use “commercially reasonable and technically feasible methods” to determine if a user is under the age of 18 (GBL section 1501(1)(a)). What are the key desired properties of an age determination method? What are key challenges to assessing any age-determination method?

- Currently, age determination can be carried out via a number of methods, including biometric assessment; assessment based on analyzing user activity; government-issued ID; attestation from a reliable third-party business with pre-existing age information, such as a bank via an issued credit card; attestation from other users; self-attestation; and cognitive tests.

- How accurate is each of these methods at determining whether a user is under the age of 18?

- What is the risk of falsification for each?

- How much does each cost, and how is cost assessed?

- How do these methods ensure that the privacy of user data is preserved?

- What data do they require to function?

- What are the risks of bias for each of these methods?

- Are these answers potentially different for social media platforms, or for certain kinds of social media platforms? Would it be more or less reliable to have other users attesting for your age in the social media context than in other online contexts?

- Are there other age-determination methods currently available? What are they? How do they compare to those previously listed?

- What age-determination methods are likely to be available in the near future? How do they compare to the methods we have listed?

- The OAG is considering a framework that would provide users a variety of options from which to select, including biometric assessment; assessment based on analyzing user activity; government-issued ID; attestation from a reliable third-party business with pre-existing age information, such as a bank via an issued credit card; attestation from other users; self-attestation; and cognitive tests. If such an approach is adopted, what would make it effective, secure, private, affordable, quick, and easy to use?

- Can any existing third-party age-determination services be used by a social media platform without needing additional efforts by the platform? What data do these services rely on? What data do they retain after age determination has taken place? How do these services demonstrate to outsiders that they have deleted information, where they represent that such deletion has occurred?

- What methods do social media platforms currently use to determine (or attempt to determine) age? Do these methods vary based on the specific industry or focus of the social media platform, or are they based on other factors?

- Some social media platforms presently attempt to determine user ages for a variety of internal purposes based on information other than self-attestation. For what purposes do such platforms currently attempt to determine age? What processes do they use to attempt to determine age? What data do these methods use to infer age? How accurate, and how precise, are such determination attempts? What factors increase or decrease the accuracy of such determination attempts?

- Many existing users of social media platforms have already self-attested to being 18 years of age or older. What data exist on the accuracy of such self-attestations? How does this compare to the accuracy of users currently self-attesting to being 13 years old?

- A number of entities currently have access to information that may reliably convey age, including banks, email providers (who may know how old an email address is), telecommunications companies, and smartphone operators. How could OAG’s regulations ensure that age determination based on attestation from such entities is secure and protects user privacy?

- How, if at all, should OAG regulations incorporate clear boundaries (bright lines) around specified levels of accuracy in assessing what age-determination methods are commercially reasonable and technically feasible? What bright lines might be appropriate? Should those bright lines vary based on characteristics of the platform in question? If so, how and why?

- What obligations should OAG regulations specify concerning how social media platforms can request age determination? How can OAG ensure that users are effectively informed of the substance of the age-determination process without creating an undue burden?

- Should OAG regulations require notice about the harms of addictive feeds? If so, what form should the notice take? What content should it include?

- Should OAG regulations require notice about specified information concerning methods, such as how fast the method takes, what data it will require, its error rate, and any bias?

- How should OAG regulations account for technological changes in available age-determination methods, or changes in users’ willingness to use certain methods?

- If OAG regulations require social media platforms to monitor browser or device signals concerning a user’s age or minor status (similar to the do-not-track or universal-opt-out signals some browsers or devices presently employ), what factors should OAG consider when specifying an appropriate standard for those browser or device signals?

- How, if at all, do online platforms currently determine age for compliance with laws against online gambling? How do platforms currently determine age for compliance with laws regarding online pornography, or the ability to enter into contracts?

- New York laws require age determination or verifying identity in many contexts offline, such as for gambling, accessing some library services, or purchasing alcohol. How accurate are these age-determination methods? What protections ensure that the data collected in age and identity determinations are not used for other purposes?

- While some social media platforms are open to the general public for all purposes, many are focused on a specific audience, such as professional networking or discussion of specific hobbies. In some cases, users may be significantly more likely to be an adult, or more likely to accurately self-attest concerning their age. How should OAG’s regulations assess the audience of a given social media platform when assessing the cost and effectiveness of age-determination methods?

- Social media platforms’ commercial and technical capabilities vary widely. What information should OAG consider for purposes of “commercially reasonable and technically feasible” concerning the size, financial resources, and technical capabilities of a social media platform platform’s ability to use some or all age-determination methods?

- How, if at all, should OAG regulations incorporate bright lines around the size, financial resources, or technical capabilities of a social media platform when assessing what age determination methods are commercially reasonable and technically feasible? What bright lines might be appropriate?

- What impact, if any, would using age-determination methods have on the safety, utility, and experience of New Yorkers using social media platforms?

- Are there some age determinations methods that would have more significant, or less significant risks?

- Are there some age determination methods that have higher risks of falsification?

- Does this vary based on the nature of the social media platform?

- Are there given classes of users, such as immigrants or LGBTQ+ users, who may be affected differently by some or all age-determination methods than other communities of New Yorkers? How can OAG regulations mitigate such impacts?

- Some New Yorkers, such as immigrant and LGBTQ+ users, may be concerned about supplying sensitive personal information for age determination. How can OAG regulations assure such New Yorkers that such information will be immediately and securely deleted?

- What are the considerations OAG should consider to ensure the security of data used in age determination?

- Are there technical mechanisms such that a user could verify that their information was successfully deleted?

- In crafting regulations, what is the best way to protect against first-party data mismanagement?

- What is the best way in crafting regulations to protect against third-party data mismanagement?

- What have we learned from experiences in other states and Europe about the most effective way to ensure that data collected for one purpose is not used for another purpose?

- What have we learned from other data-minimization-enforcement regimes about the most effective, enforceable rules regarding not retaining data beyond specified purposes? In what other contexts are online services trusted to immediately delete data after a single use?

- If OAG regulations required social media platforms to disclose that they would be fined up to $5,000 each time they failed to immediately delete information used for age determination, would this help assure users that their personal information will be deleted?

- Taking all the foregoing into account, what are the most effective, secure, private, affordable, quick, and easy-to-use, commercially reasonable, and technically feasible current methods for any form of online age determination?

- The SAFE for Kids Act permits social media platforms to provide children with an addictive feed or overnight notifications only when the platform had obtained “verifiable parental consent” (GBL sections 1501(2), 1502). What methods do websites, online services, online applications, mobile applications, or connected devices presently use to determine whether an individual is the parent or legal guardian of a given user? What costs — either to the parent or to the website, online service, online application, mobile application, or connected device — are associated with these methods? What information do they rely on?

- What methods do websites, online services, online applications, mobile applications, or connected devices currently use to process and verify parental requests for their child’s data to be deleted? How might these procedures prove effective or ineffective for obtaining verifiable parental consent?

- What obligations should OAG regulations specify concerning how social media platforms request verifiable parental consent? How can OAG ensure that parents are effectively informed of what they are being asked to consent to without being unduly burdened?

- How can OAG ensure that parents are likely to understand the risks before providing consent?

- Should OAG regulations require notice about the harms of addictive feeds?

- What lessons can be learned from regulations regarding other harmful products, like cigarettes, alcohol, and gambling, about communicating harms and limiting promotion to children?

- Should OAG regulations require that consent be requested in a standalone fashion, disconnected from any other requests?

- Should OAG regulations mandate that parents must be able to give, reject, or withdraw consent without having to create a social media account?

- What methods should OAG regulations specify may or must be made available to parents to provide, reject, or withdraw consent?

- How can OAG regulations ensure that requests for verifiable consent, and any accompanying disclosures, are understandable and effective for parents from all New York communities?

- Many of the same concerns about protecting user privacy while determining age exist for parental consent. How can OAG regulations assure New Yorkers that information provided for parental consent will be immediately and securely deleted?

- What are the most effective and secure methods that currently exist for any form of obtaining parental consent?

- Are there other factors or considerations related to obtaining verifiable parental consent that OAG regulations should consider?

- The definition of an addictive feed in GBL section 1500(1)(c)-(d) includes exceptions for personalization in response to “user-selected privacy or accessibility settings, or technical information concerning the user’s device.” Are there specific kinds of settings or technical information of particular importance that may require express permission in OAG regulations?

- GBL section 1506(1), which requires requests for parental consent to be made available in the 12 most commonly spoken languages in New York, grants OAG authority to promulgate regulations adding additional requirements. What, if any, regulations should OAG draft concerning language access. Why?

- Should OAG require disclosure in specific dialects of languages? If so, which dialects? Why?

- What information concerning the harms of addictive feeds to minors should OAG consider when drafting its regulations?

- What factors or considerations should OAG take into account to preserve existing safeguards for children on social media platforms?

Child Data Protection Act

Advanced Notice of Proposed Rulemaking pursuant to New York General Business Law section 899-ee et seq.

The New York State Office of the Attorney General (OAG) is issuing this Advanced Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (ANPRM) to solicit comments, data, and other information to assist the office in crafting rules to protect children's privacy pursuant to New York General Business Law section 899-ee et seq. (GBL section 899-ee).[2]

In recognition of the unique privacy needs of children, the New York legislature passed the Child Data Protection Act (CDPA) to ensure the privacy and safety of the personal data of New Yorkers under the age of 18. The CDPA primarily applies to applies to operators of a “website, online service, online application, mobile application, or connected device, or portion thereof” who “alone or jointly with others, controls the purposes and means of processing... data that identifies or could reasonably be linked, directly or indirectly, with a specific natural person or device” where both of the following are true (GBL section 899-ee(1)-(4)):

- The operator actually knows that the data is from a minor user.

- The data is collected from a website, online service, online application, mobile application, or connected device, or portion thereof that is “primarily directed to minors.”

If a user’s device “communicates or signals that the user is or shall be treated as a minor,” the operator must “treat that user” as a minor (GBL section 899-ii(1)).

The CDPA requires such operators to process, and permits most third parties to process, the personal information of known minors, or data from services primarily directed to minors, only where they are permitted under the federal Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act and its enacting regulations (U.S.C. section 6502) for children under the age of 13, or for children between 13 and 17, where it is either “strictly necessary” for a number of specified purposes, or the operator has obtained “informed consent” (GBL section 899-ff(1)).

Those specified purposes include (GBL section 899-ff(2)):

- “providing or maintaining a specific product or service requested by the [user]”

- “conducting the operator's internal business operations...”

- “identifying and repairing technical errors that impair existing or intended functionality”

- “protecting against malicious, fraudulent, or illegal activity”

- “investigating, establishing, exercising, preparing for, or defending legal claims”

- “complying with federal, state, or local laws, rules, or regulations”

- “complying with a civil, criminal, or regulatory inquiry, investigation, subpoena, or summons by federal, state, local, or other governmental authorities”

- “detecting, responding to, or preventing security incidents or threats”

- “protecting the vital interests of a natural person”

Requests for “informed consent” must be made pursuant to a number of requirements to ensure that users are able to effectively assess the purpose of the processing and understand their rights (GBL section 899-ff(3)(a)). Consent must be freely revocable, and requests for consent may not be made more than once a year (GBLsection 899-ff(3)(b)-(c)). In addition, if a user’s device “communicates or signals” that the user does not consent to processing, the operator must adhere to that communication or signal (GBL section 899-ff(3)(d), (ii)(2)). Operators may not “withhold, degrade, lower the quality, or increase the price” of their services because of an inability to obtain consent (GBL section 899-ff(4)).

Operators may not purchase or sell, or allow another to purchase or sell, the personal data of minors (GBL section 899-ff(5)).

Where an operator relies upon a “processor” to process the data of minors on their behalf, they must enter into a “written, binding agreement” requiring the processor to process minor data only pursuant to the directives of the operator or as required by law, and to otherwise assist the operator in ensuring compliance with the CDPA (GBL section 899-gg).

When a minor user turns 18 or older, the privacy protections of the CDPA continue to apply to any data gathered while the user was a minor unless the operator receives informed consent for additional processing (GBL section 899-hh).

Third-party operators — such as the operator of a pixel or API that gathers data from a website run by another operator — are treated as operators under the CDPA and may process the personal information of minors only with informed consent from the user (if 13 or older) or the user’s parent (if under 13), with three exceptions (GBL section 899-jj):

- where the data is strictly necessary for a purpose specified in GBL section 899-ff(2)

- where the third-party operator “received reasonable written representations from the operator through whom they are collecting the data that the user provided informed consent for such processing”

- where they lack both “actual knowledge that the [user] is a minor; and” do not know that they are collecting data from a website, online service, online application, mobile application, or connected device, or portion thereof, [that] is primarily directed to minors

Questions for Public Comment

The OAG is issuing this ANPRM to solicit comments, including personal experiences, research, technology standards, and industry information that will assist OAG in determining what rulemaking will be most important to effectuate the purposes of the CDPA. The OAG seeks the broadest participation in the rulemaking and encourages all interested parties to submit written comments. In particular, OAG seeks comment from interested parties — including New York parents and children, consumer advocacy groups, privacy advocacy groups, industry participants, and other members of the public — on the following questions. Please provide, where appropriate, examples, data, and analysis to back up your comments.

Submit comments to ChildDataProtection@ag.ny.gov by September 30, 2024.

- The Child Data Protection Act applies where either operators have actual knowledge that a given user is a minor, or the operators’ websites or online services are “primarily directed to minors” (GBL section 899-ee(1)). What factors should OAG regulations assess when determining if a website or online service is primarily directed to minors?

- At present, the federal Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act’s enacting regulations assess whether a website or online service is “directed to children” under 13 based on the following non-exclusive factors: “subject matter, visual content, use of animated characters or child-oriented activities and incentives, music or other audio content, age of models, presence of child celebrities or celebrities who appeal to children, language or other characteristics of the Web site or online service, as well as whether advertising promoting or appearing on the Web site or online service is directed to children... [and] consider competent and reliable empirical evidence regarding audience composition, and evidence regarding the intended audience” (16 CFR section 312.2). Should OAG’s assess a different set of factors when assessing what is attractive to minors under the age of 13? Why or why not?

- The interests of older teens are likely to be largely identical to the interests of many adults, so websites and online services directed at adults will generally also be of significant interest to many older teens. How should OAG regulations ensure that websites and online services that are directed to adults are not deemed “primarily directed to minors” based on these overlapping interests?

- What factors would be relevant in assessing whether websites or online services are primarily directed to minors or older teens?

- What factors would be relevant in assessing whether websites or online services are primarily directed to minors or younger teens?

- Should OAG regulations include separate tests for different age groups, or a single test with factors stretching across age groups? If the regulations should treat age groups differently, how and why?

- Are there factors that are more relevant than others in assessing whether a website or online service is primarily directed to minors? Which ones? Why? Is there research or data that shows the importance of these factors? How should OAG regulations emphasize these factors?

- Should OAG regulations treat websites or online services differently where they become primarily directed to minors based on changes outside of their control — such as minors becoming attracted to new kinds of content, or a large number of minors independently finding the service — compared to those that were always primarily directed to minors or that sought out minors for their audience?

- What does the current research on marketing, development psychology, or other fields say or suggest about what kinds of content or experiences minors are particularly attracted to? What does the current research say or suggest about what kinds of content or experiences are designed primarily for minors? How does the research differentiate between minors of different ages or age groups? How should this research be incorporated into OAG regulations?

- What other laws, regulations, or industry standards exist that contemplate whether material may be targeted towards minors? Do they impose restrictions on targeting towards minors of any age, or do they apply only to certain ages or age groups? On what are they based? How effective have they been at capturing the empirical behavior of minors?

- The Child Data Protection Act’s obligations include website or online services, “or portions thereof,” that are primarily directed to minors. Should OAG regulations distinguish portions created by an operator and portions created by users of the website or online service? If so, how?

- How should OAG regulations concerning the definition of personal data account for anonymized or deidentified data that could potentially still be re-linked to a specific individual (GBL section 899-ee(4))?

- The CDPA’s definition of “sell” includes sharing personal data for “monetary or other valuable consideration” (GBL section 899-ee(7)). Are there examples of ways operators may share personal data that do not constitute a sale that should be explicitly noted in OAG regulations?

- What factors should OAG consider in defining what processing is “strictly necessary” to be permissible without requiring specific consent? N.Y. GBL sections 899-ff(1)(b), 899-ff(2).

- The CDPA permits operators to process personal data without needing to obtain consent when “providing or maintaining a specific product or service requested by the covered user.” GBL section 899-ff(2)(a). Many modern online services bundle products or services together, or include ancillary products or services in response to a user request: for example, a cooking app might automatically display nearby groceries with relevant ingredients when a user looks up a recipe, which would require processing the user’s geolocation information. What factors should OAG consider in determining whether bundled products or services are incorporated into the “product or service requested by the covered user”?

- The CDPA permits processing for “internal business operations.” Are there examples of permissible processing pursuant to internal business operations that should be explicitly noted in OAG’s regulations? GBL section 899-ff(2)(b).

- The CDPA permits teenagers (minors between the ages of 13 and 17) to provide informed consent to processing on their own behalf (GBL section 899-ff(3)). What obligations should OAG regulations specify concerning the manner in which operators may request such informed consent?

- How can OAG ensure that teenagers are provided with notices that will effectively convey the potential risks, costs, or benefits of requested processing?

- How should OAG regulations concerning requests for informed consent balance between providing users with necessary and relevant information, but not overwhelming users with too much information or too many choices?

- How should OAG regulations treat requests for informed consent to multiple different kinds of processing at the same time or in short succession?

- What methods should OAG regulations specify may or must be made available to withdraw informed consent when it is provided?

- How can OAG regulations ensure that requests for informed consent, and any accompanying disclosures, are understandable and effective for New York teenagers from all communities?

- What standards should OAG regulations set for acceptable device communications or signals that a user is a minor or consents or refuses to consent to data processing? GBL sections 899-ff, 899-ii.

- Are there other factors or considerations related to obtaining informed consent that OAG regulations should consider?

- What methods do websites, online services, online applications, mobile applications, or connected devices presently use to determine whether an individual is the parent or legal guardian of a given user? What costs — to either the parent or the website, online service, online application, mobile application, or connected device — are associated with these methods? What information do they rely on?

- Where a device communicates that a user is under the age of 13 pursuant to GBL section 899-ii(1), how can OAG regulations ensure that any communications consenting to processing under GBL section 899-ii(2) satisfy the parental consent requirements of 15 U.S.C. section 6502 and its implementing regulations?

- What are the most effective and secure methods that currently exist for any form of obtaining parental consent?

- Are there other factors or considerations related to obtaining parental consent that OAG regulations should consider?

[1] The SAFE for Kids Act also provides OAG with authority to “promulgate such rules and regulations as are necessary to effectuate and enforce” the Act. GBL section 1505.

[2] The statute authorizes OAG to “promulgate such rules and regulations as are necessary to effectuate and enforce the provisions of this article.” GBL section 899-kk.

Understand web tracking to keep your family safe

Websites and apps often use cookies and other technologies to generate customized ads and otherwise track your and your kids’ activity. We created this guide to help you understand how companies may monitor you, so you can better safeguard your privacy.

A consumer guide to web tracking

Protect your privacy by managing how businesses monitor you online.